BLOG

Our health stories

Increasing the scope of practice of New Zealand’s pharmacists - are we falling behind?

Literature evidence indicates that many community pharmacists and intern pharmacists are interested in offering more clinical services but need time and a supportive management structure to release them from the core task of dispensing and to facilitate the completion of the specific training prerequisites. Health policy with a greater strategic emphasis on funding extended services and training, and developing technician roles to free up pharmacists’ time, should act as a lever to direct focus.

Are New Zealand’s Home and Community Support Services in peril?

Some of the key issues facing HCSS in New Zealand include increasing demand in numbers and complexity, inconsistent, fragmented service delivery, funding arrangements that create inefficiencies in the system, high HCSS workforce turnover, and insufficient funding to increase supply to a level that will meet the growing demand. There have been calls for new ways of working in home and community support services (HCSS) to respond to the multiple and growing demands on HCSS.

How do we support improvement of health and wellbeing standards among children and youth in New Zealand?

There are about 800,000 young people in New Zealand. Our young people, as the next generation, shape the future of Aotearoa New Zealand. Young people deserve to be supported and empowered to reach their full potential and enhance their mana. Having healthy young people ensures a healthier society for New Zealand, both now and in the future.

What strategies could help reduce strain on health services in New Zealand?

It is entirely plausible that NZ may continue to feel the COVID-19 effect for many years to come. We need to look at a long-term approach to address the current shortfalls and mitigate risks when it comes to workforce planning, succession planning, developing different models of care, and building health infrastructure.

How do we accelerate healthcare interoperability standards in New Zealand?

Lack of interoperability is widely acknowledged to be a critical barrier for the adoption and deployment of digital health technologies and for the digital transformation of healthcare. Addressing and overcoming this barrier requires awareness and cooperation among all stakeholders. This should start with a shared understanding of the relevant interoperability standards in digital health.

Is timeliness an issue with Pharmac’s cost-driven-decision-making process?

Medicines are a vital part of modern health care. Medicines make a significant contribution to health outcomes. The question of how to give patients access to them in a way that the health system can afford has exercised policy-makers and politicians for many years.

Pharmac was established in June 1993. It is a unique agency. It is the only organisation in the world that manages a fixed budget set by the government and decides which medicines will be funded.

How can we improve health sector productivity and health outcomes in New Zealand?

The demand pressures on the health sector are real, and innovative new models of primary healthcare offer opportunities to address them. There is still more work to be done, but there is some evidence that innovation in primary healthcare delivery has the potential to drive both productivity improvement and better outcomes across the wider health system.

Question: What short/long term policies should we utilise to clear New Zealand’s healthcare service backlog?

As COVID-19 cases started to rise in early 2020 and hospitalisation rates increased, health systems began to postpone non-emergency procedures to keep capacity available for COVID-19 patients, and to avoid elective patients being infected. This has subsequently led to longer waiting lists and waiting times in virtually all countries.

Question: Are New Zealand’s palliative care services equipped to cope with rising demand?

Palliative care is care for people of all ages with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition, which aims to optimise an individual’s quality of life until death and support the individual’s family, whānau and other caregivers.

Question: Is the “Hospital at home” model a worthwhile alternative in New Zealand?

Demand for hospital beds has been steadily increasing over recent years and often exceeds the existing capacity. Optimising people’s access to acute care within community health services, and supporting acute hospital flow by avoiding admission and providing early support to patients and their whānau will take the pressure off the system.

Can we strike a balance between sharing and constraining health information in New Zealand?

All those involved in the health data cycle need to understand their rights and responsibilities and build models of trust to provide an environment that facilitates the responsible use of health data with robust identity protection, and collective and participatory ethical data sharing mechanisms. Rather than focussing on individual experiences, this requires a society-centred design approach. A responsible flow of data will benefit humanity through medical discovery, and potentially improve population health.

The deep end of the mental health crisis in New Zealand. Why has the pattern seen a reversal?

New Zealand’s youth suicide rates are the highest in the OECD and have recently been deemed a ‘suicide crisis’ by the Prime Minister’s former Chief Science Advisor. New Zealand’s youth suicide rates are particularly high for young, indigenous Māori and Pacific Island people. The response to this, in the last several decades, has been an increasing commitment to a mental health approach to understanding and dealing with suicide and concerns to prevent the ‘normalisation’ of suicide as a way of coping with adverse circumstances.

The Disability sector - Are we addressing the barriers for disabled people accessing healthcare in New Zealand?

Disability is not about having a specific medical condition, it is about living with activity limitations or functional difficulties that affect everyday life, and older people are more likely than younger people to be affected. Disabled people experience health inequities due to barriers existing within multiple social determinants of health such as education, employment, housing, as well as bias within the health systems (e.g., access to quality health services). To improve outcomes for disabled people, the health system will need to improve its understanding of different population groups, involve people in designing services and provide a range of services that are appropriate for the people who use them.

We need to talk about men’s health in New Zealand - Are we tackling the root causes?

Men’s health is partly a product of biology, social expectations and systemic discrimination variable of access and quality of care, as well as a consequence of masculinity (a set of male attributes, behaviours and roles): the invulnerable approach to diet and activity, and the ‘man up’ approach to health.

To improve men’s health, it is beneficial to raise men’s health awareness by enabling men to define what health means to them, improve access to healthcare resources, particularly avoiding environments, terminology or judgments that might be negative about masculinity.

Is the ‘great resignation’ affecting New Zealand’s healthcare workforce?

Across the globe, the ‘Great Resignation’, defined as the mass exodus of unsatisfied workers, has hit few industries harder than healthcare. According to some reports, the field has lost 20% of its workforce. It has hit healthcare workers in a unique way, with abuse, misinformation, burnout and trauma on a massive scale.

Should New Zealanders avoid dental health care due to cost?

In New Zealand, a trip to the dentist is a significant expense for many and one that is put off for as long as possible. The risk for dental problems is determined in early childhood and can be intergenerational. Those born into disadvantaged families go on to have greater rates of tooth decay as adults. Tooth decay is the main reason why children older than 1 year require pre-arranged hospital treatment. After respiratory conditions, dental treatments have often been the second-biggest cause of hospital admissions.

New Zealand needs to increase our spend on preventive dental care to save on the high costs of dental interventions. Currently, population-level prevention represents a very small component of the public dental health care budget.

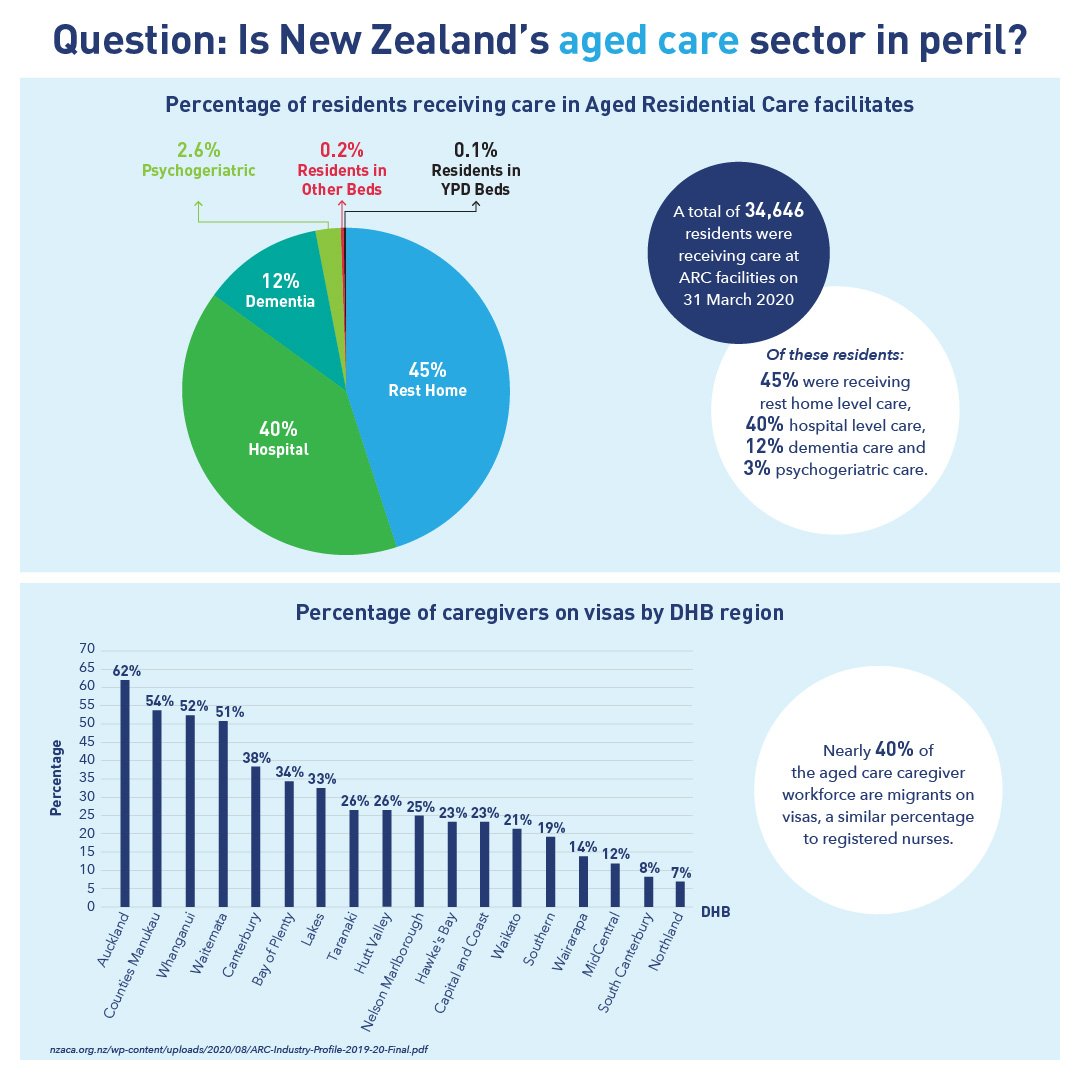

Is New Zealand’s aged care sector in peril?

Our blog post this week takes a look at New Zealand's aged care sector. Chronic understaffing has put immense strain on the providers and there is a dire need for change.

Since prevention is better than cure, do we invest enough towards prevention strategies in New Zealand?

Prevention is better than cure. Successive policy makers and healthcare providers have recognised this reality. Yet, most have failed to prioritise prevention. Priority needs to be given to interventions and diagnostics with the greatest chance of the largest equitable effects. But which are they and how are they most effectively introduced?

Even though high-quality, reliable information is a key enabler for effective, efficient and patient-centered healthcare, the value of information in general, and the value of diagnostic information (VODI) specifically, have not been part of the discussion until recently.

Does New Zealand need to rethink the approach to addressing treatment gaps within mental health services?

We understand now that we can’t medicate, or treat our way out of the epidemic of mental distress. “Meds-and-beds” is not the solution. So, how then do we start to tackle this problem?

How can New Zealand’s health sector embrace the complexity around workforce shortage and rebuild the workforce pipeline?

A healthcare investment is the smart investment. The health workforce is a national resource; a resource that is valuable to the community in terms of the benefit derived by the community from a well-trained health workforce.