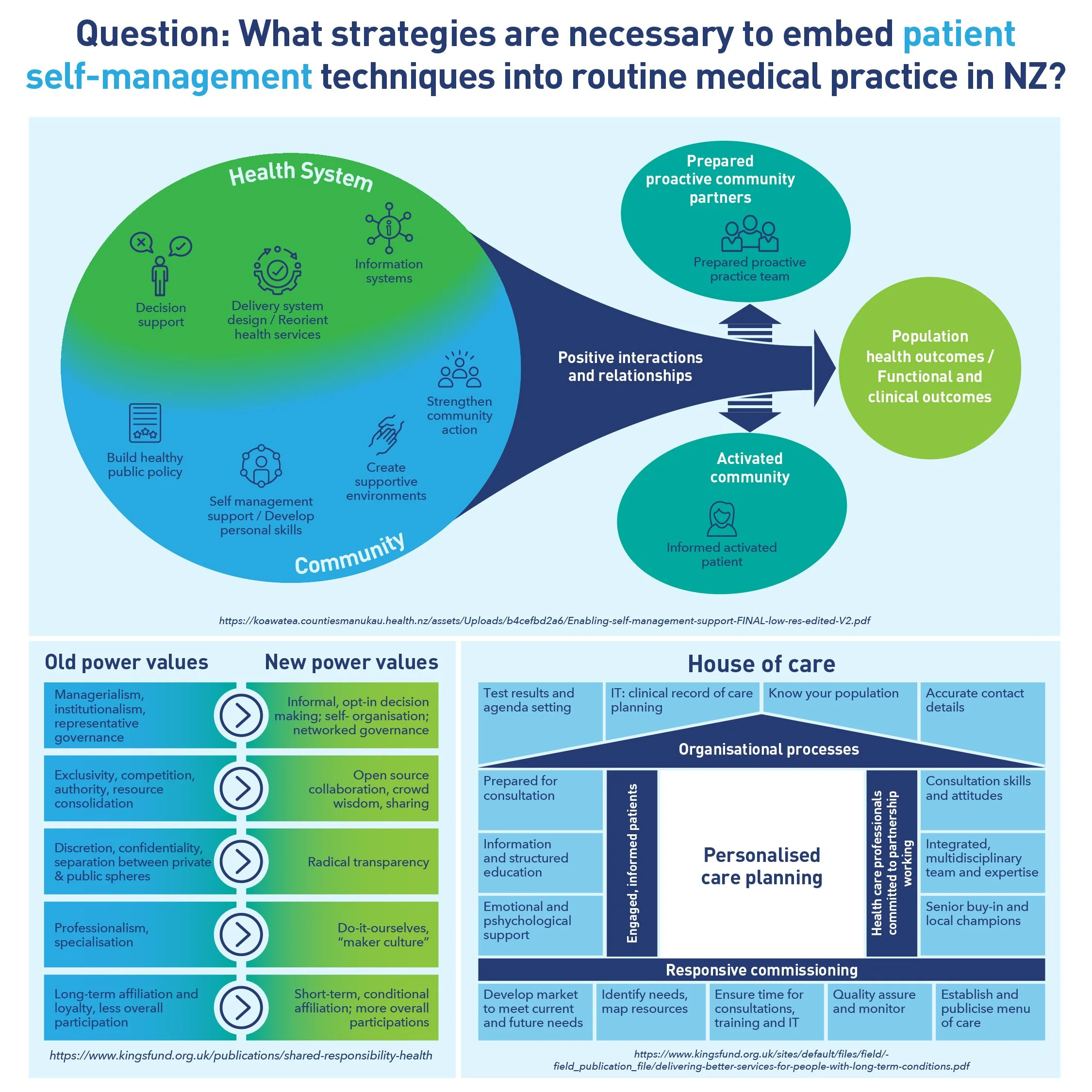

What strategies are necessary to embed patient self-management techniques into routine medical practice in NZ?

Health systems risk being overwhelmed by the significant impact of long-term conditions (LTCs). This is sometimes referred to the “healthcare equivalent to climate change”.

Ongoing illness is affecting a growing number of older people, especially those who are poor and belong to ethnic minorities. Many experience multiple concurrent conditions that require complex care with different treatments and involve a range of various health-care providers.

LTCs are rising in New Zealand and many people have several LTCs. These include diabetes, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, mental illness, chronic pain, chronic kidney disease, dementia and others. Supporting people to self-manage is a critical part of coping with the growing burden of LTCs.

People with LTCs often feel they are a problem, a burden to themselves, their family, friends and even health providers. Patients, and providers, often struggle to “control” these conditions and “failed management” is repeatedly cast as a patient problem, even though providers can have deficits in knowledge and confidence, face time constraints and find care coordination a challenge.

There is an urgent need to transform how community-based primary healthcare supports people with LTCs to self-manage, take more control over their health and improve their health outcomes. Providers must be aware of patients’ needs and preferences to be effective in improving patients’ health.

For some, the term ‘self-management’ is problematic, suggesting a focus on the ‘self’ as an individual at the expense of important social contexts; particularly family/whānau. In fact, self-management theory takes a holistic view that is aware of the need to engage people with LTCs within their wider social context.

Internationally, self-management is recognised as one of the critical components in improving healthcare for people with LTCs. It is fundamental to the health and wellbeing of people with LTCs, and enables the health system to make the best use of increasingly scarce resources.