Governance in healthcare series Part I: Clinical Governance

Written by Tom Varghese

Governance is a framework that accounts for all the processes of governing organisations and businesses. The role of governance in healthcare organisations looks a bit different than it does in other types of industries.

A healthcare board of directors and executive management are in charge of all aspects of governance. One aspect of governance is the clinical side. Maintaining and improving the quality and safety of patient care falls under clinical governance. Business performance, compliance with laws and regulations, as well as ethics fall under corporate governance. Clinical and corporate governance systems are intrinsically linked, although each has its own objectives.

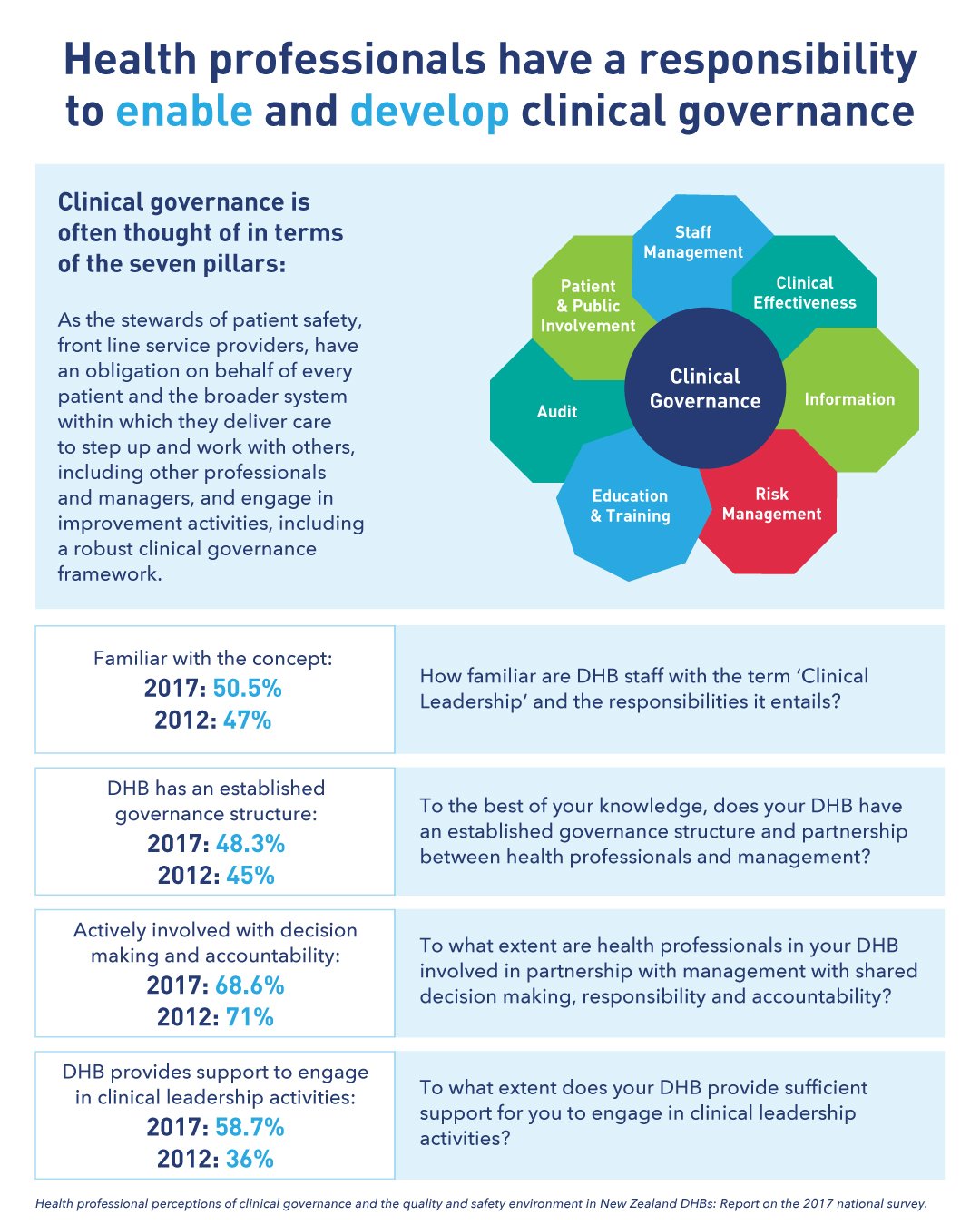

Going into the 2010s, there was a strong focus on clinical governance and leadership in the New Zealand health sector. An effective clinical governance framework has four ‘building blocks’: consumer engagement, clinical effectiveness, an engaged and effective workforce and a commitment to working on quality improvement.

Clinical governance is an organisation-wide approach to the continuous quality improvement of clinical services. It is larger in scope than any single quality improvement initiative, committee or service. It involves the systematic joining-up of all patient safety and quality improvement initiatives within a health organisation. In practice, it requires clinicians to be engaged in both the clinical and management structure of their health organisation to contribute to the mission, goals and values of that organisation. It is also about managers engaging more with clinicians and enabling them to be involved.

Although the structures are in place, clinical leadership is often compromised by the competing demands of clinical work and the time imperative of ongoing change. Sector feedback reveals that major decisions are still made by a few service leaders with middle level managers and clinicians often required to demonstrate leadership by implementing changes that they don't completely understand or agree with. Robust decision making is not the norm and there is a tendency to jump from one crisis to another without taking stock. The concept of clinical governance is often unknown to most clinicians. Further, middle level managers are often unsupported in decision making.

Across NZ’s public health system, we have a complex governance framework. It is not yet clear if the public are engaged in the elected model of DHB Boards or if elections produce well equipped boards. Clinical governance is multi-faceted and will take time to embed. That said, if clinical governance in New Zealand is to advance, there is arguably a demand for a more supportive environment for this to happen. This means encouragement and support from across the sector, with advice and guidance from the centre as well as clear commitment and support from the DHBs.